Suche

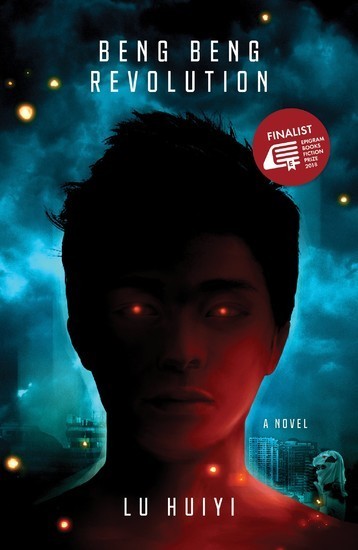

Beng Beng Revolution

E-Book (EPUB)

2019 Epigram Books

218 Seiten

Sprache: English

ISBN: 978-981-4845-17-5

Beng Hock and his brother, Beng Huat (who prefers to go by Archibald), find themselves navigating a tumultuous Singapore in the near future that has run out of oil and gas. Running afoul of the growing gangs could mean slavery or death, jobs are scarce and food scarcer, and home is a crumbling shanty-town behind the City Hall Steam-Engine Station.

And as if these changes aren't drastic enough, a great power awakens inside Beng Hock, and he must learn how to control it before it destroys everyone and everything in his way.

Lu Huiyi holds a degree in English Literature from the National University of Singapore, and is currently pursuing a post-graduate course at Singapore Management University. Beng Beng Revolution is her first novel.

Unterstützte Lesegerätegruppen: PC/MAC/eReader/Tablet

And as if these changes aren't drastic enough, a great power awakens inside Beng Hock, and he must learn how to control it before it destroys everyone and everything in his way.

Lu Huiyi holds a degree in English Literature from the National University of Singapore, and is currently pursuing a post-graduate course at Singapore Management University. Beng Beng Revolution is her first novel.

Unterstützte Lesegerätegruppen: PC/MAC/eReader/Tablet

Chapter 1

" Whatever affects the world is going to affect us," said Father one day, as he nursed his morning coffee. "It's all linked. We can't run away."

The news was flashing on television, but the volume was muted because Mother was still sleeping in. Huat had long since gone out, because he had a strange penchant for doing meaningful things with his life. Beng, who was slightly less inclined towards productivity, made himself comfortable at the dining table and glanced at the screen. Another war, another conflict, another crisis.

"There, see?" said Father, gesturing at the screen. "All linked."

The Deprivation had begun in the Middle East, early in the year. Nobody had really thought the day would come when national leaders would declare, in sombre, bewildered tones, that their societies were finally running out of raw energy to harvest and use. But there they were, and the rest of the world watched in shock and dismay as oil prices soared.

"So you think the Deprivation is going to affect us?" Beng said, watching the programme with more concern than comprehension.

"If it's as bad as some people say, then maybe," Father said, but he didn't look all that worried, as though he didn't quite believe it himself.

"They always say until so bad, but-" Grandfather shrugged and took a swig of his coffee. His eyes fluttered shut in a display of bliss somewhat disproportionate to the consumption of three-in-one instant coffee off the discount rack. Beng had an enduring suspicion that Grandfather had a habit of lacing his coffee with something out of the liquor cabinet, and nine in the morning was really pushing it, even for Grandfather. But Grandfather had turned vice into a subtle art and was very good at not getting caught.

"They've been saying it's bad for a very long time, though," Beng persisted. "Don't you think we should worry?"

Father and Grandfather exchanged good-humoured looks of derision. Or at least, Father's look was one of good-humoured derision. Grandfather was probably just good-humoured because he was buzzed as hell.

"Worry for what?" said Father. "It's not like we can do anything even if it's bad."

He got up to refill his mug. Beng shrugged and reached for another piece of toast. It was a pleasant, lazy kind of weekend morning, and Beng had errands to run and a social appointment or two to get to. The conversation subsided into the realm of the frivolous and was soon forgotten.

But Beng, as it turned out, was eventually proven right-although Father, as it turned out, wasn't wrong about that last bit too.

"I'm sure the world won't just run out of oil," said Huat that same night, rolling his eyes. Beng frowned. Huat was a full eight years older than Beng was, and the only one in the family with a university degree and a freshly-landed executive job. This apparently allowed him to make declarations about the state of the world with far greater arrogance than the average man, but not necessarily a corresponding degree of accuracy.

Father huffed a little unhappily as Huat's voice cut above the drama serial that he was watching on television. It was some kind of period drama-Father was a sucker for Chinese imperial dramas and watched them religiously every evening, though for some reason he didn't like acknowledging it to everyone else. Possibly because Mother tended to make snide remarks about people hooked on outdated shows that just recycled the same plots over and over again, and because Grandfather tended to laugh uproariously at every tragic exile or imprisonment scene that the dramas offered. By way of self-defence, Father usually claimed that he only watched it because people had left the television on, which was technically not untrue if by "people" he meant himself.

"Why are we talking about politics? TV t

" Whatever affects the world is going to affect us," said Father one day, as he nursed his morning coffee. "It's all linked. We can't run away."

The news was flashing on television, but the volume was muted because Mother was still sleeping in. Huat had long since gone out, because he had a strange penchant for doing meaningful things with his life. Beng, who was slightly less inclined towards productivity, made himself comfortable at the dining table and glanced at the screen. Another war, another conflict, another crisis.

"There, see?" said Father, gesturing at the screen. "All linked."

The Deprivation had begun in the Middle East, early in the year. Nobody had really thought the day would come when national leaders would declare, in sombre, bewildered tones, that their societies were finally running out of raw energy to harvest and use. But there they were, and the rest of the world watched in shock and dismay as oil prices soared.

"So you think the Deprivation is going to affect us?" Beng said, watching the programme with more concern than comprehension.

"If it's as bad as some people say, then maybe," Father said, but he didn't look all that worried, as though he didn't quite believe it himself.

"They always say until so bad, but-" Grandfather shrugged and took a swig of his coffee. His eyes fluttered shut in a display of bliss somewhat disproportionate to the consumption of three-in-one instant coffee off the discount rack. Beng had an enduring suspicion that Grandfather had a habit of lacing his coffee with something out of the liquor cabinet, and nine in the morning was really pushing it, even for Grandfather. But Grandfather had turned vice into a subtle art and was very good at not getting caught.

"They've been saying it's bad for a very long time, though," Beng persisted. "Don't you think we should worry?"

Father and Grandfather exchanged good-humoured looks of derision. Or at least, Father's look was one of good-humoured derision. Grandfather was probably just good-humoured because he was buzzed as hell.

"Worry for what?" said Father. "It's not like we can do anything even if it's bad."

He got up to refill his mug. Beng shrugged and reached for another piece of toast. It was a pleasant, lazy kind of weekend morning, and Beng had errands to run and a social appointment or two to get to. The conversation subsided into the realm of the frivolous and was soon forgotten.

But Beng, as it turned out, was eventually proven right-although Father, as it turned out, wasn't wrong about that last bit too.

"I'm sure the world won't just run out of oil," said Huat that same night, rolling his eyes. Beng frowned. Huat was a full eight years older than Beng was, and the only one in the family with a university degree and a freshly-landed executive job. This apparently allowed him to make declarations about the state of the world with far greater arrogance than the average man, but not necessarily a corresponding degree of accuracy.

Father huffed a little unhappily as Huat's voice cut above the drama serial that he was watching on television. It was some kind of period drama-Father was a sucker for Chinese imperial dramas and watched them religiously every evening, though for some reason he didn't like acknowledging it to everyone else. Possibly because Mother tended to make snide remarks about people hooked on outdated shows that just recycled the same plots over and over again, and because Grandfather tended to laugh uproariously at every tragic exile or imprisonment scene that the dramas offered. By way of self-defence, Father usually claimed that he only watched it because people had left the television on, which was technically not untrue if by "people" he meant himself.

"Why are we talking about politics? TV t